|

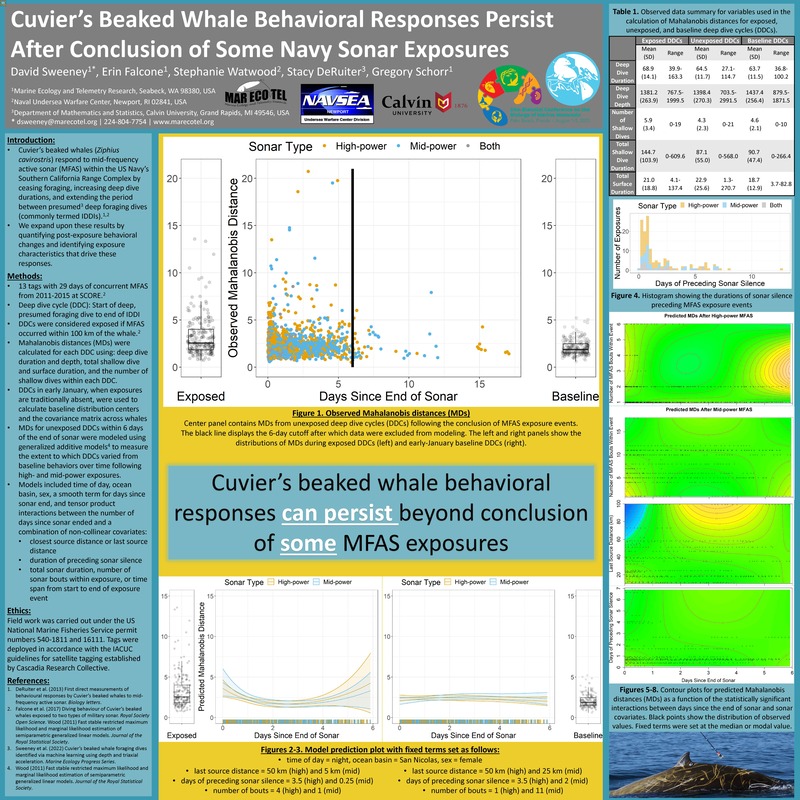

MarEcoTel is participating in the 24th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals in Palm Beach, Florida this week both in person and virtually. Our scientists are apart of many research projects in collaboration with several organizations. Please check out some of our presentations! Insights into foraging behavior from multi-day sound recording tag deployments on Cuvier's beaked whales in the Southern California Bight Shannon Coates, Greg Schorr, Stephanie Watwood, Brenda Rone, Russ Andrews, David Sweeney, Mark Johnson, Karin Dolan, and Stacy DeRuiter Scratching at the surfacings: exploring extended surface intervals in Cuvier's beaked whales Erin Falcone, Greg Schorr, David Sweeney, Brenda Rone, Stacy DeRuiter, Shannon Coates, Russ Andrews, and Stephanie Watwood Re-sighting histories of dart-attached tags in Cuvier's beaked whales and fin whales in the Eastern Pacific Ocean Erin Keene, Erin Falcone, Greg Schorr, Brenda Rone, Gustavo Cardenas-Hinojosa, and Russ Andrews Movements and diving behavior of Risso's dolphins in the Southern California Bight Brenda Rone, David Sweeney, Erin Falcone, Stephanie Watwood, and Greg Schorr Context Matters: multi-day to multi-week sound and movement recordings reveal individual variation in responses of Cuvier's beaked whales to navy sonar Greg Schorr, Stacy DeRuiter, Brenda Rone, David Sweeney, Russ Andrews, Karin Dolan, Erin Falcone, Shannon Coates, and Stephanie Watwood Cuvier's beaked whale behavioral responses persist after conclusion of some navy sonar exposures David Sweeney, Erin Falcone, Stephanie Watwood, Stacy DeRuiter, and Greg Schorr Use of navy training ranges and NMFS's Biologically Important Areas by blue and fin whales off the U.S. West Coast Barbara Lagerquist, Ladd Irvine, Tom Follett, Erin Falcone, Greg Schorr, Bruce Mate, and Daniel Palacios Vulnerability of North Atlantic right whales to entanglement and vessel collision risks in the Gulf of St. Lawrence: insights from their diving behavior V. Harvey, V. Lesage, Russ Andrews, K. Sorochan, S. Plourde, J. Gosselin, A. Mosnier, and C. Johnson Vulnerability of U.S. marine mammal stocks in the Pacific and Arctic to climate change M. Lettrich et al. Using a Mask R-CNN neural network framework to detect Steller sea lions in autonomous camera images Alexey Altukhov, Russ Andrews, Ivan Usatov, Vladimir Burkanov, and Thomas Gelatt Steller sea lion brand detection and identification on aerial images using deep learning approach Ivan Usatov, Alexey Altukhov, Vladimir Burkanov, Russ Andrews, and Thomas Gelatt Exploring the use of seabirds as dynamic ocean management tools to mitigate anthropogenic risk to large whales Tammy Silva, Kevin Powers, Jooke Robbins, Regina Asmutis-Silva, Timothy Cole, Alex Hill, Laura Howes, Charles Mayo, Dianna Schulte, Michael Thompson, Linda Welch, Alexandre Zerbini, and David Wiley Diving behavior of humpback whales during their southbound migration in the Western South Atlantic Ocean Erika Coelho, Solene Derville, Vinicius Maia, Artur Andriolo, Federico Sucunza, Daniel Daniewicz, and Alexandre Zerbini Development and characterization of a non-antibiotic antimicrobial polydopamine surface coating for use in marine mammal conservation Ariana Smies, Jeremy Wales, Maureen Hennenfent, Bruce Lee, Jooke Robbins, Alexandre Zerbini, and Rupak Rajachar In the wake of small cetaceans: can targeted eDNA sampling support stock structure analysis for small or elusive cetaceans? Kim Parsons, Sam May, Zachary Gold, Kimberly Goetz, Alexandre Zerbini, Christine Gabriele, Jan Straley, John Moran, Marilyn Dahlheim, Linda Park, and Phillip Morin El ñino affects reproduction and survival of humpack whales in the Brazilian breeding ground Mariana Neves, Leonardo Wedekin, Alexandre Zerbini, Daniel Danilewicz, Julio Baumgarten, and Paulo Inácio Prado Using density surface models in a highly complex survey area (Southeast Alaska) to estimate humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) abundance and distribution

Abigail Schiffmiller, Greg Breed, Kimberly Goetz, and Alexandre Zerbini

2 Comments

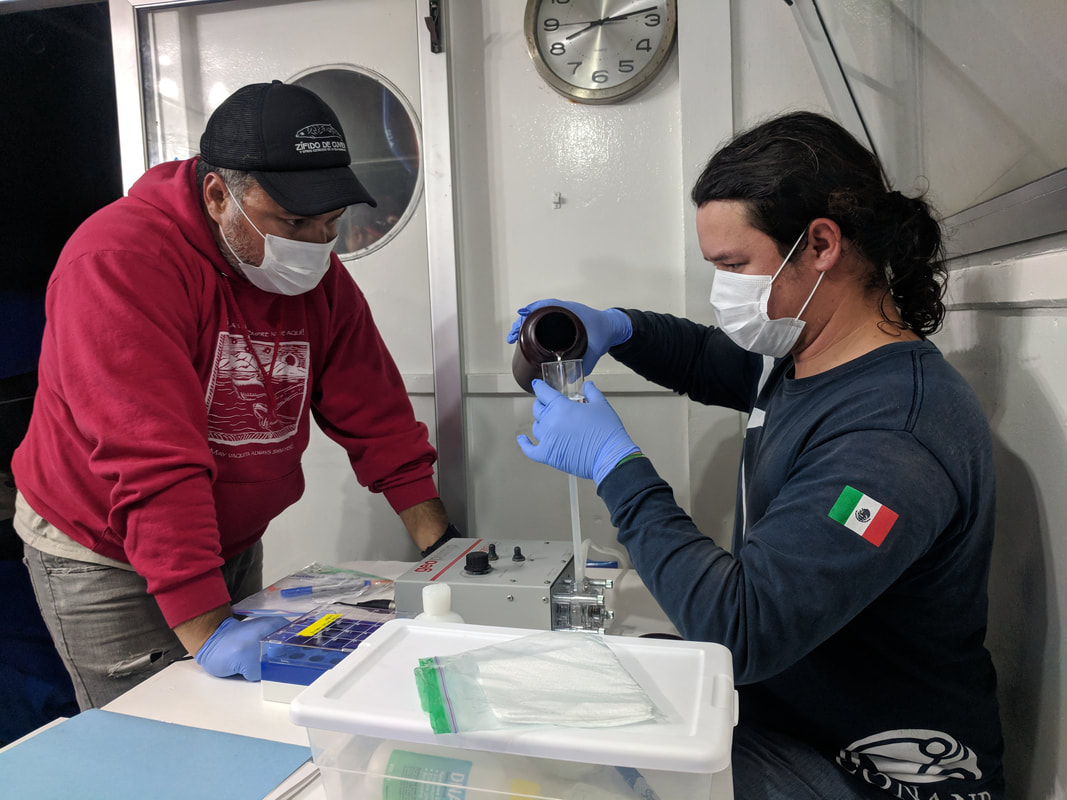

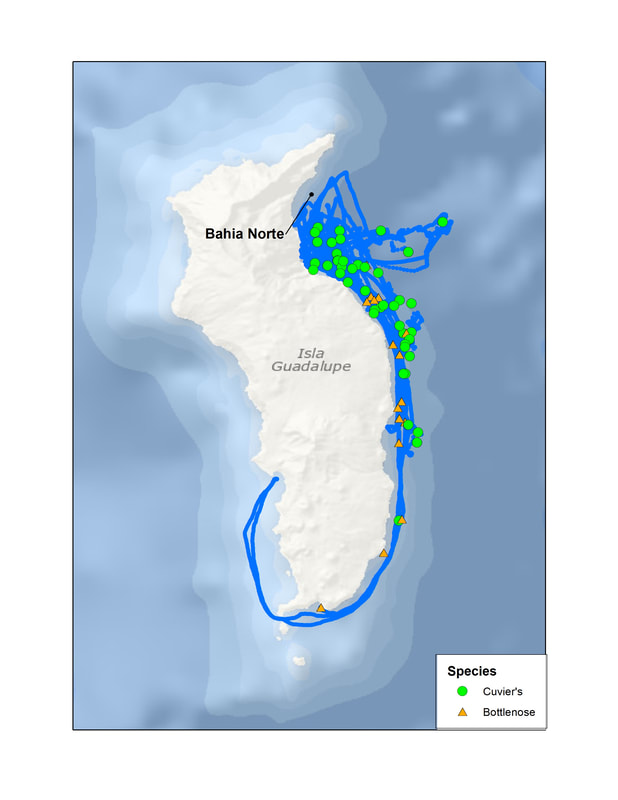

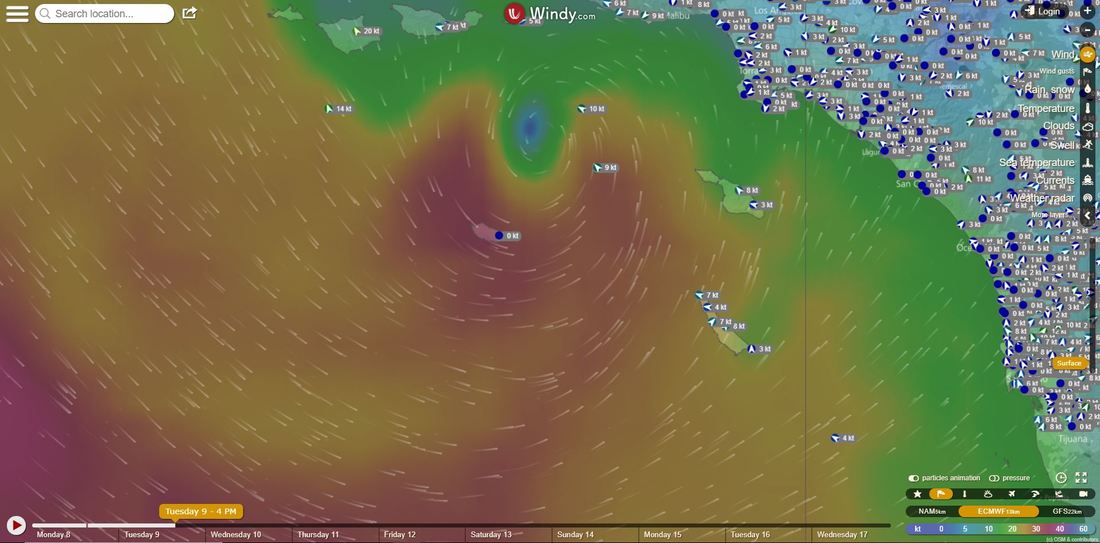

During May 2019, we completed our second field effort of the Guadalupe Island comparative study. This work is in collaboration with our colleagues Gustavo Cárdenas-Hinojosa, Lorenzo Rojas Bracho, and Andrea Bonilla. To learn about the background on this project and the results from our first field effort, check out our previous blog post here. In typical island magic, our trip started out with a bang. After picking up the panga from Campo Oeste, we headed to the north end of the island on the east side to Bahía Norte. It was a windy day and as we tucked into the small lee of the bay, Brenda was searching to the stern just at a group of five Cuvier’s beaked whales broke the surface about 300 meters away. Thank you for delivering immediately, Guadalupe Island! The weather was surprisingly poor throughout our trip. We had a lot of wind. We had rain. We had cold. Down jackets may have been worn on numerous occasions (it was over 40 degrees colder than Washington at times). The upside was that with rain comes beautiful rainbows. So, we’ve established the weather was poor BUT in spite of this, the trip was quite successful and it is not often one can say this--which should help explain how truly unique and special this place is. Despite several attempts to make it offshore or south, we were always forced back into what we referred to as our “postage stamp” of a survey area within Bahía Norte. Fortunately, this is a hot spot for whale activity. Often times, we would just drop anchor, stand watch and patiently wait for the animals to come to us. Brenda and Greg were enjoying this method tremendously since the work off San Clemente Island, California requires approximately 180 kilometers of surveying (with no protection from the weather) and does not always result in beaked whale sightings. In the nine days we spent at the island, we deployed four location and dive behavior LIMPET satellite tags on two adult males, one female with an older calf, and one sub-adult. This now brings the project total to eight tags deployed. Thanks to the skilled eyes and memory of Andrea, we were able to get immediate identifications of individuals, an incredible asset for this project for a number of reasons, one of which is for selecting candidates for tagging and biopsy. We had several resightings from our October 2018 survey including a female with a new calf. In fact, we documented several mom/calf pairs including two mom/neonates (recently born with fetal folds still visible)! In total, we had 38 sightings of 111 individuals with many of these being resights of the same individuals throughout the survey. We are looking forward to the photo-ID results once Andrea, Erin Keene (MarEcoTel), Brenda and Erin Falcone (MarEcoTel) have processed and matched the images to the Guadalupe and California catalogs. We collected a number of eDNA water and biopsy samples. We were also very fortunate to have Jay Barlow from Southwest Fisheries Science Center onboard with us. Several acoustic devices were deployed during the transits to and from Ensenada and while working in Bahía Norte. On the very last day when we had to return the panga and were limited by time due to the tides, we finally had the first calm, windless day (of course). We ran the canyon offshore and within a short time we had two Cuvier’s sightings totaling three animals. Only one animal was close enough for a photo and we identified it as a new animal for the trip and a resighting from our October survey. Just a side jaunt out from the island proved quite fruitful. We can only imagine what we would have found if we had more weather windows during this trip. While returning the panga, we were fortunate to have an opportunity to meet the director of the Biosphere Reserve, Marisol Torres. Our next field effort off Guadalupe Island will be in September. We would like to thank our funder, the Office of Naval Research. Thank you to Marisol Torres, Director of the Biosphere Reserve who supports our work in the Reserve. Thank you to Raul Urias and the community of Campo Oeste for providing an excellent panga and help with logistics. Thank you to Scott Carnahan, owner of M/V Storm, for continuing to support our research and providing a stellar research platform, Captain and crew. Thank you to Frank and Jane Falcone for supporting our work in all the ways they continue to do so. Without all of these organizations and people, this work would not be possible. Last, but certainly not least, we would like to thank everyone involved in this survey. MarEcoTel feels very lucky to have the opportunity to work with such kind, enthusiastic, smart people and they all made this trip phenomenal.  From Left down to Right up: Celso Nieto (engineer), Brenda Rone (MarEcoTel), Daniel Martinez (CONANP), Martin Rodriguez (fisherman), Andrea Bonilla (Oceanides), Gustavo Cárdenas-Hinojosa (CONABIO), Jay Barlow (SWFSC), Noé Lucero (Captain), Olegario León (cook), Greg Schorr (MarEcoTel), Tony Rielas (mate). Photo: Gregory S. Schorr AuthorBrenda Rone The effects of repeated exposure to anthropogenic sources, such as Navy Mid-Frequency Active (MFA) sonar, need to be measured across both short-term and long-term spectra. To evaluate potential impacts of these sources on a routinely exposed population of whales, a parallel study of a nearby population where they are not used should be conducted to provide a baseline of unexposed behavior and population health. In October, we headed South of the Border to begin a collaborative study looking at the demographics and dive behaviors of Cuvier’s beaked whales at Guadalupe Island, Mexico. The purpose of this project is to better understand the impacts of sonar use on the whales at the Navy range off San Clemente Island, CA by studying animals at a comparative site, Guadalupe Island, that have little to no exposure. We are working with Gustavo Cárdenas-Hinojosa and Dr. Lorenzo Rojas Bracho from the Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). Guadalupe Island is located 150 miles off the west coast of Mexico’s Baja California peninsula. It measures 22 miles long and 6 miles wide with the highest peak, Monte Agusta, rising to 4,259 ft. It is a volcanic island consisting of two shield volcanos (named for its low profile resembling a warrior’s shield) with captivating colors and mesmerizing geological patterns that reveal its formation to the trained eye. Greg’s geology skills came in very handy! It’s desert-like appearance today is a stark contrast to its forested history, before lumber became a hot commodity. Hunters nearly wiped out both the endemic Guadalupe fur seal and the northern elephant seal populations that bred there. Goats replaced wild species which severely impacted the survival of both flora and fauna. Today, thanks to protection from the Mexican government, both seal species are thriving on the island. There are several endemic bird species including the Townsend’s and Ainley’s storm petrels that nest on a few islets on the southern end of the island. Guadalupe Island is one of the top five places in the world to see great white sharks. The water is crystal clear with visibility upwards of 100-150 feet. Research indicates that this is a mating ground, and with seals providing a plentiful food source, it is definitely sharky waters. It’s not recommended to go frolicking carefree in the water to cool off. We were lucky to have a few beautiful, curious individuals check us out. A close encounter with a great white shark. Video: Christian Torres The island and the surrounding waters were designated as a biosphere reserve in 2005. For the most part, it is wild and uninhabited except for a fishing community of approximately 200 individuals (abalone and lobster) that live on the island for 10 months out of the year at Campo Oeste. It wasn’t until recent years that Cuvier’s beaked whales were recognized as another regular species inhabiting the waters around Guadalupe Island. When several underwater videos documented them nearly a decade ago, researchers including Gustavo Cárdenas-Hinojosa decided to conduct a survey to see how many animals were in the area. Fast forward 8-years and their efforts have demonstrated the presence of Cuvier’s beaked whales within close proximity to Guadalupe Island during multiple seasons, with some individuals spotted numerous times suggesting site-fidelity. Currently, there are 82 individuals in the catalog with new individuals added every trip. This is where MarEcoTel enters the picture. When assessing the nature and degree of anthropogenic impacts on a population, a key question is “compared to what?” This is particularly difficult to evaluate when no data exist for the population of interest prior to the introduction of the activity. Such is the case with Cuvier's beaked whales that live in and near the Southern California Anti-Submarine Warfare Range (SOAR), where they are frequently exposed to Mid-Frequency Active (MFA) sonar during routine military training exercises- the likes of which have been associated with mass strandings of this species elsewhere in the world. While there is a growing body of behavioral and demographic data on the SOAR population, there is little or no data from an ecologically-similar population of this species that is not regularly exposed to MFA sonar to which these data can be compared. Such an approach is proving highly valuable for evaluating impacts to Blainville's beaked whales at a training range in the Bahamas, led by researcher Diane Claridge with the Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organization. In October, we conducted our first joint field effort with Gustavo and his team to determine whether Guadalupe Island might serve as a comparative study site for SOAR. Our goals for this project are to:

In the late afternoon, Brenda spotted several blows close to shore. She remembers asking just how close to shore do they see Cuvier’s. “Very close.” was the reply. She said, “Well, these look like they are on the beach!” Sure enough, we had a group of seven and away we went on the panga. Three sightings (10 individuals), day one; and if you think that sounds amazing, the following day, which was our first full day of effort, we had 11 sightings (34 individuals). This trip was filled with wondrous examples like this. There was that one late evening, while sitting on anchor, when we could hear the exhalations of a group passing close by us, or that casual first sighting of the day while having early morning coffee on the back deck without even trying to look for animals. Compared to our California work where our average survey day is 100 nm of dedicated survey effort, and we often do not encounter beaked whales, this is definitely paradise. We were very fortunate to have those first few days of calm weather. It shows just what can be accomplished when the weather cooperates. Unfortunately, we were fighting the effects of hurricane Sergio, and towards the end of our survey the winds wrapped around the island and we had lost our lee. Despite this, we accomplished quite a bit. We documented 38 sightings (101 individuals) (Figure 1), deployed 4 satellite tags, collected two biopsy samples, one eDNA sample, one squid sample, and deployed 2 C-PODs (passive acoustic recorders). The only additional cetacean species we documented were bottlenose dolphins (Figure 1). What was astonishing was that we had more Cuvier’s than bottlenose dolphins! To put the number of Cuvier’s sightings into perspective, at SOAR, our average encounter rate is one sighting for every 18 hours of search effort. Needless to say, we are thrilled to have this opportunity to conduct research in such a special and extraordinary place. The four satellite tags were deployed on four different individuals with transmission durations ranging from 18 to 26 days; they collected 1,256 hours of diving behavior from three of the four tagged whales. The basic pattern observed from Cuvier’s beaked whales in other regions was apparent, with deep, presumed foraging dives generally separated by a series of shallow dives. The individual median deep dive durations ranged from 56.6 – 74.0 min (max = 149.2 min). Individual median deep dive depths ranged from 991.5-1135.5 m (max = 2799.5 m). The median Inter-Deep Dive Interval ranged from 101.9 – 160.1 min; the longest time between presumed foraging dives was 485 min (8.1 hrs). Deployment of a location and dive behavior LIMPET satellite tag. Video: Veronica Morales Photographic matching identified 27 unique individuals. Individuals identified were matched back to an existing photo-ID catalog from Guadalupe Island, which includes 82 individuals from previous efforts and opportunistic photographs. Recaptures of individual whales span up to 11 years, with some individuals having been resighted 19 times, suggesting a high degree of site-fidelity. A comparison of whales identified at Guadalupe Island to those photographed in and around SOAR has not documented any individual movements between study areas to date. Our next field effort off Guadalupe Island will take place in May 2019. We are looking forward to working with our colleagues, friends, collaborators, and the crew from the M/V Storm again! We would like to thank our funder, the Office of Naval Research.  We are very grateful for this fantastic and talented group of lovely souls. We are missing some very important persons from this picture, the hardworking crew of the Storm. This trip would not have been a success without their hard work, fantastic food, and expertise. We look forward to reuniting with everyone soon! Front and Photographer: Christian Torres; Second Row: Greg Schorr, Anaid Urban, Brenda Rone; Third Row: Jenny Trickey, Veronica Morales; Fourth Row: Gustavo Cárdenas-Hinojosa, Andrea Bonilla; Boat Driver: Martín Rodriguez Congratulations! Happy Birthday! Happy Valentine’s Day! Happy Graduation! You’re Special! It’s a girl! What do these all have in common? These were all tokens of happiness, love and all good things to celebrate.

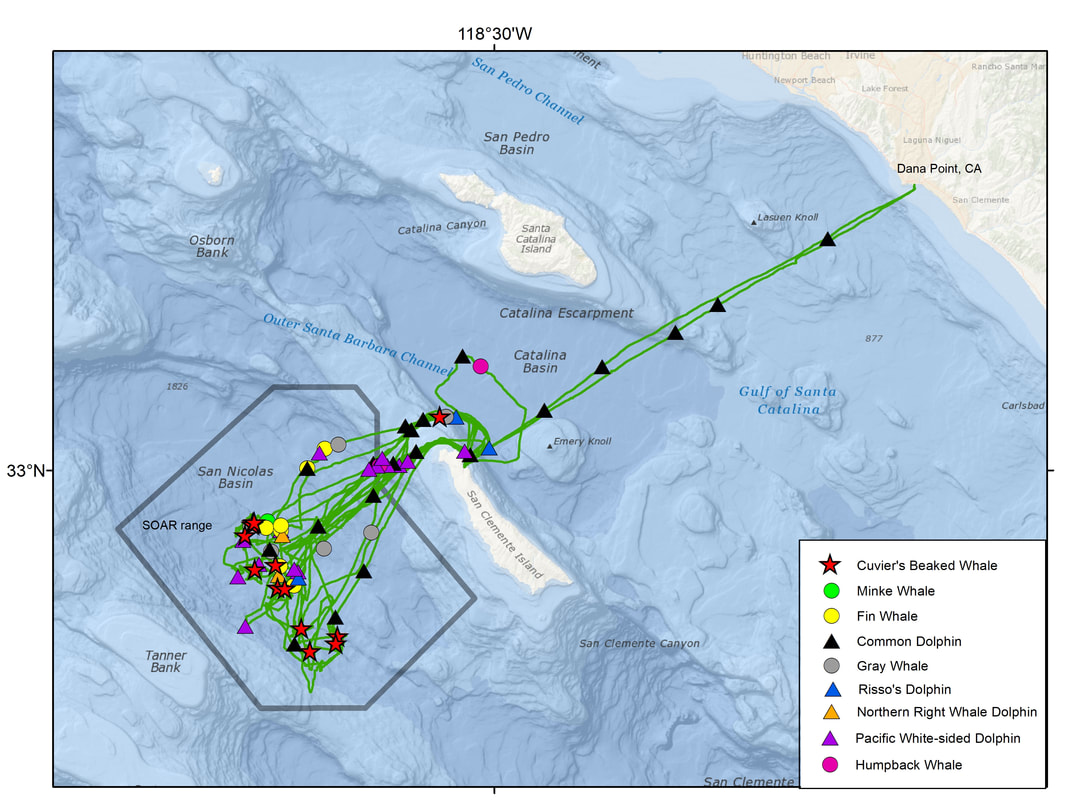

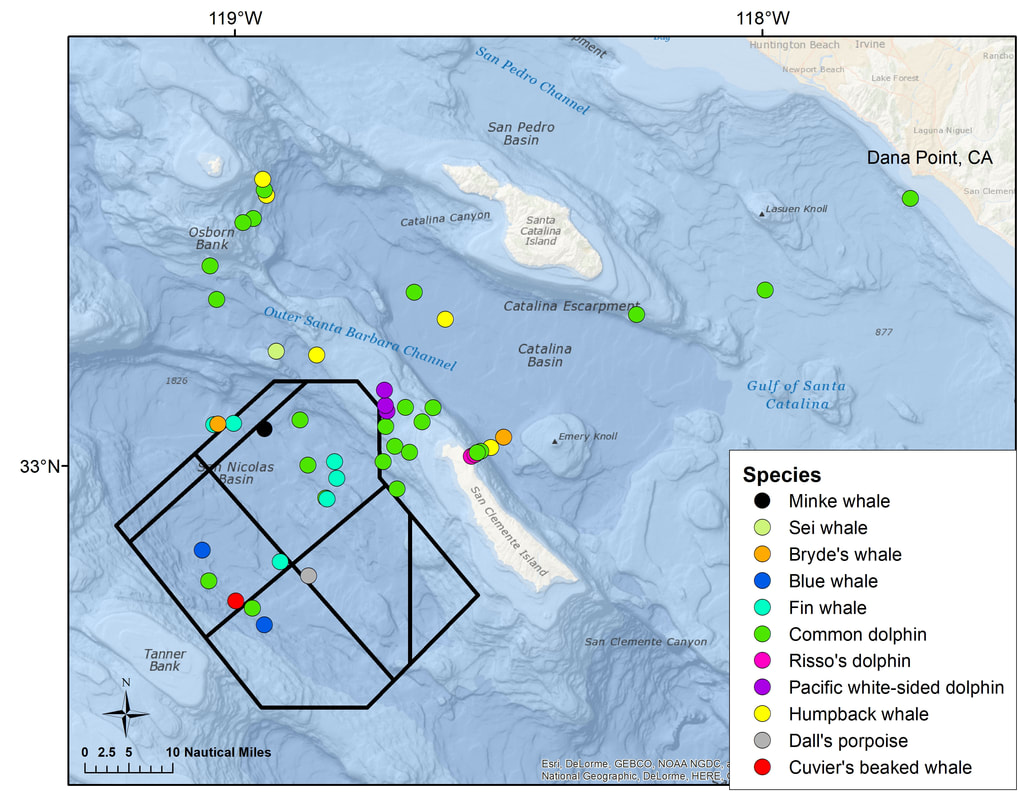

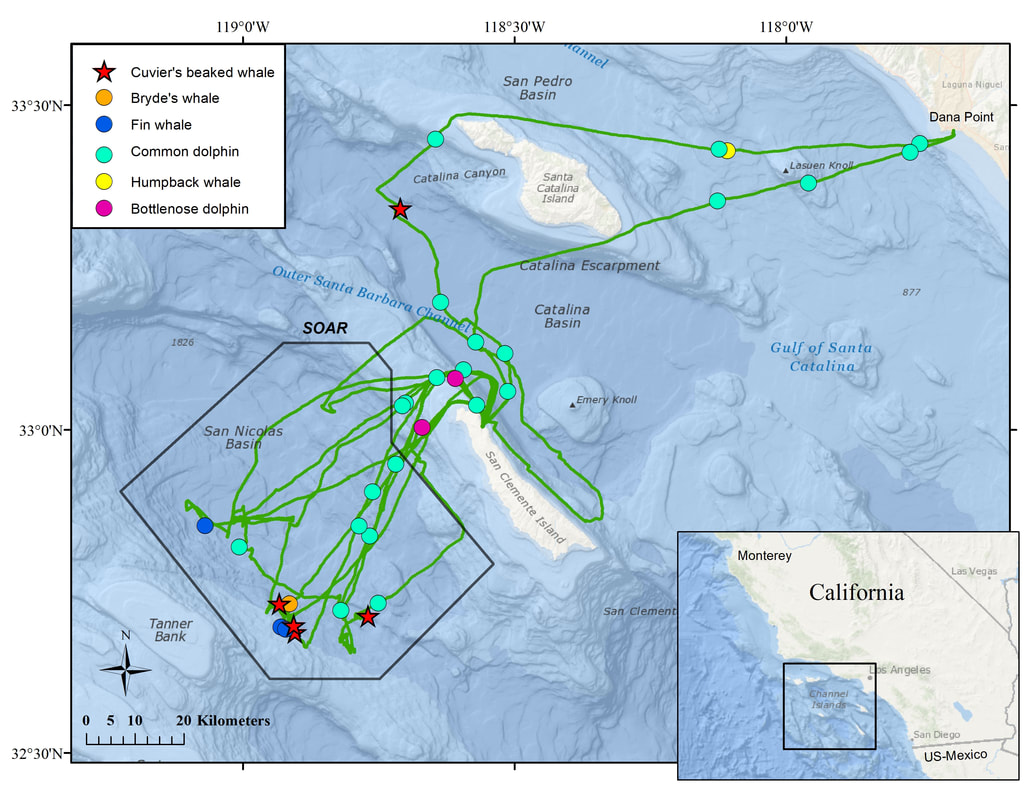

21. What is this number? It’s the number of mylar balloons we collected in April 2017 during an 8 day survey. This does not include the numerous latex balloons we picked up as well. At least triple this number and that is what we typically collect during our surveys when they occur just after a holiday like Valentine’s Day. This is just from what we see while surveying our tiny space in this vast ocean and what we have time to pick up. Why be so negative about balloons? Well, once they have served their purpose, they are trash, trash that is unnecessarily polluting the environment. Aside from showing disrespect to this beautiful planet we are fighting to protect, releasing balloons kill wildlife, both terrestrial and marine. Turtles mistake these shiny symbols of human joy for jellyfish. Birds get entangled in balloon ribbon. Big horn sheep ingest latex balloons instead of foliage. Both types of balloons have been found in the stomachs of whales and dolphins. This list of examples goes on and on…… People can argue that latex balloons are biodegradable and therefore “environmentally friendly”, but during that lengthy breakdown process, they wreak havoc wherever they land. From this point on, instead of just picking up balloons, we started documenting them in our database to continue to raise awareness to this problem. For those that ask what they can do to help the environment, this is another example of a small change, with major positive results. If you must use balloons to express your joy, please be sure they are never released into the air either intentionally or by accident, and dispose of them properly. While out on a stroll on the beach or on your favorite trails and you come across balloons (or any trash), remember how deadly they become once they land and pick them up. Let's continue to teach respect for this planet and spread the word! We are back home after completing our first field effort of 2018 on the Navy SOAR range off San Clemente Island in SoCal. This field effort was slightly longer than our typical projects in order to maximize the time we had on range while Navy activities were on a hiatus. We had a mixed bag of weather during this trip. We were plagued with thick fog for a number of days and endured a strong storm that forced us off the water for two days, but we also scored a couple of what we consider “good beaked whale weather” days with light winds, visibility and minimal swell which balanced out the productivity. You would think fog would be problematic when locating animals. It definitely provides an element of complication to an already difficult task and when winds decide to join in, it makes locating beaked whales next to impossible (unless we get lucky). Not only do we lose sight, we lose sound. Listening for animals to exhale when they surface from a dive, particularly with beaked whales, is one of the most effective ways to locate them. So, while we were visually impaired for a number of days, when we had light winds, we were still successful in locating Cuvier’s beaked whales due in big part to the expert “ears” we had from M3R (Marine Mammal Monitoring on Navy Ranges) who listened for beaked whale clicks on the hydrophones and provided us the best position to wait for the animals to surface after their long dives. During this project we had 12 days on the water totaling 106 hours of effort, covered 925 nautical miles, documented 9 species (Cuvier’s beaked, minke, fin, gray, and humpback whales, common, Northern right whale, Pacific white-sided, and Risso’s dolphins) for a total of 69 sightings of 2,356 individuals (Figure 1). We also collected genetic samples from two fin whales and one Northern right whale dolphin which will contribute to a number of studies including stock structure, stress hormones, and sex determination. We had a grand total of 13 encounters totaling 36 individuals (with some repeat sightings) of Cuvier’s beaked whales on 8 of the 9 days we had focused effort on the range, including a surprising sighting of 3 individuals just north of the island in 700 m of water (Figure 1). They are typically encountered in depths greater than 1000 m. We were able to photograph nearly all animals and deployed a medium-duration archival tag on one individual. This was a very successful trip for beaked whale sightings especially when you compare it to our last effort in November of 2017 when we had one brief sighting of one animal. Additional highlights included several sightings of Pacific white-sided dolphins and a very large group of Northern right whale dolphins estimated at 500 individuals.  In addition, we deployed a drifting acoustic buoy in several locations on range in collaboration with Dr. Jay Barlow of Southwest Fisheries Science Center. We were fortunate to have him out with us for three of the days, as he was of tremendous help and also provided some luck. We deployed a tag on the first day he arrived (Thanks Jay!). He will be looking for beaked whale vocalizations in the form of clicks which commence on foraging dives (they use sound to echolocate on prey including squid and fish) and can derive a density estimate based on the number of individual animal clicks identified within that area. We will be back down on San Clemente Island in February to continue our research in support of several projects. MarEcoTel would like to thank Living Marine Resources, Naval Undersea Warfare Center, Southern California Offshore Range, San Clemente Island personnel, and Frank and Jane Falcone for support, assistance, and collaboration.

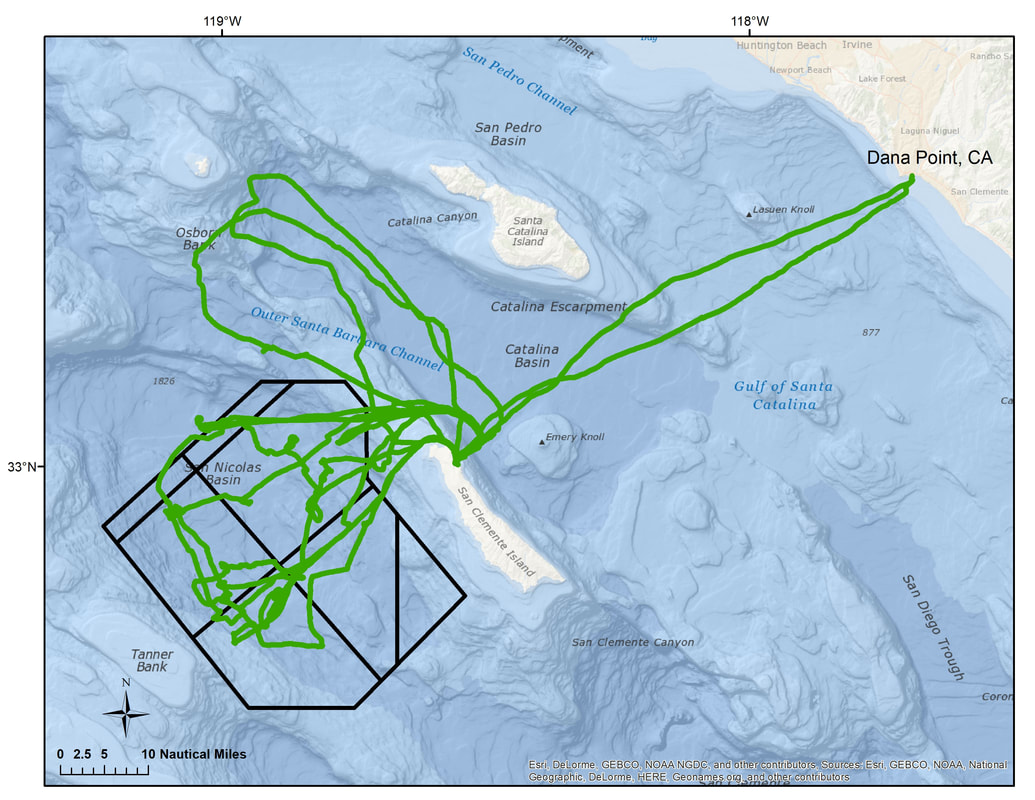

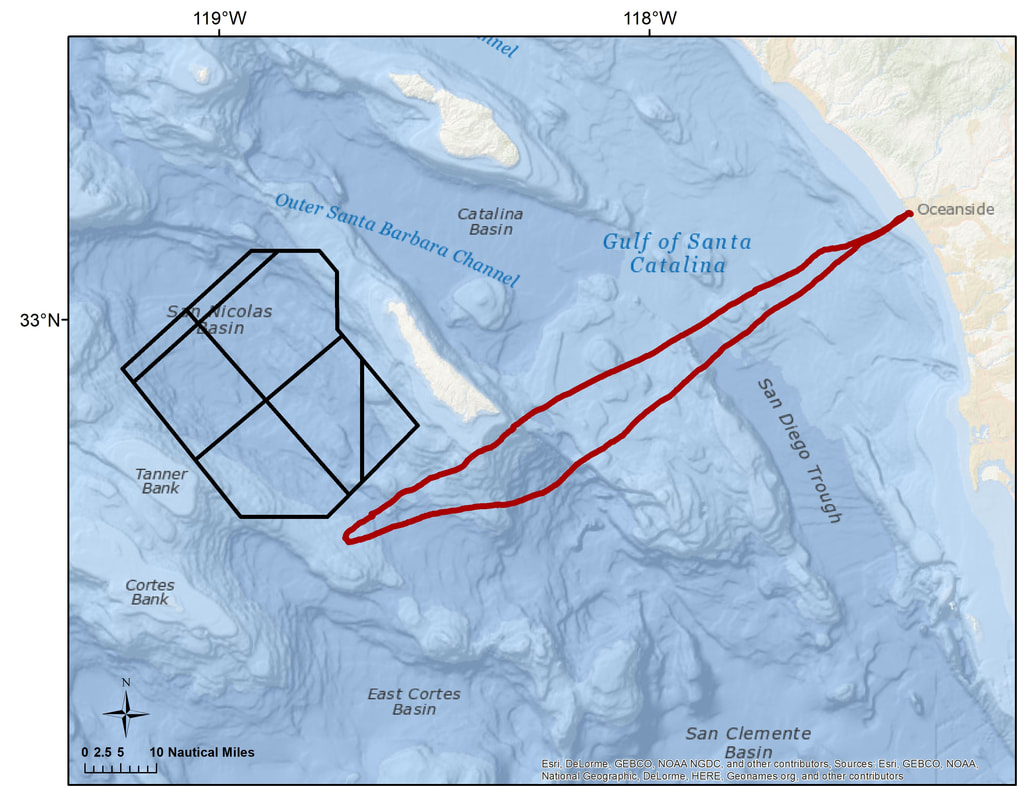

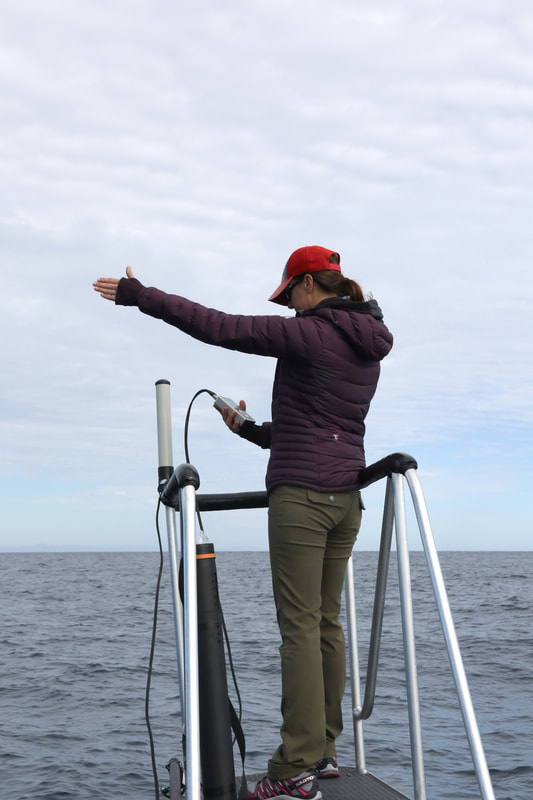

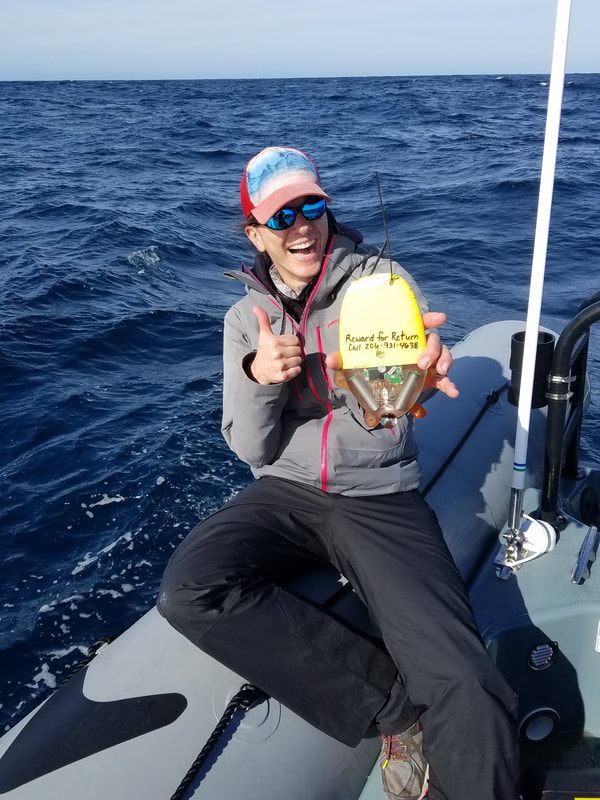

In November, we completed our fifth and final field effort for 2017. This was the first research trip for our new vessel R/V Phoenix. When we arrived in California at the start, we had to hit the ground running in overdrive (although when don’t we!) in order to finish up the last round of installations and configurations in order to have her science ready. With tasks completed in time, we packed her up with our equipment and food and were immediately pleased with what felt like an infinite amount of storage space (don’t worry R/V Physalus, we still love you). With her ample space for equipment and persons, her speed to get us on scene, and her comfort when working in rough conditions, she quickly proved to be an invaluable asset to our research and conservation efforts. Greg and R/V Phoenix in Wilson Cove, San Clemente Island. During this project, we spent 73 hours on the water and surveyed 868 nautical miles. We documented 53 sightings of 11 species: minke whale, sei whale, Bryde’s whale, fin whale, blue whale, humpback whale, Cuvier’s beaked whale, Risso’s dolphin, common dolphin, Dall’s porpoise, and Pacific white-sided dolphin. Survey effort and sightings from the November 2017 project. It was a quiet project for beaked whales. In fact, we only had one encounter of a single animal for one surfacing despite acoustic detections. We define “beaked whale weather” as a Beaufort seastate 2 or less with minimal swell. They are cryptic animals and near glass calm conditions are needed to see, hear, and approach in time before they slip back down for another dive. These dives can range from 20 min to 2 hours depending on their behavioral state with surface times only averaging 2 minutes. The lack of visual sightings for this trip can be attributed to a fair chunk of uncooperative weather. Even rain made an appearance which is really nothing abnormal for us Pacific Northwesterners, but on one lucky morning, we were gifted one of the most vibrant rainbows either of us have seen. Unfortunately, there wasn't a beaked whale at the end of it. Searching, searching, and more searching for beaked whales. Greg remains focused despite the background show. We had a few noteworthy encounters this trip. The first was of a fluking fin whale. Unlike whales such as humpbacks, blues, and grays, this is not a common occurrence for this species. In fact, for one of us, this was only the second time this was observed, the first time being 19 years ago in another ocean! This whale is a genetically confirmed female identified as ID326 in our catalog and has been sighted in Southern California nearly every year since 2009. This whale is so unique that when we posted this fluke photo, she was immediately recognized as “Flukey” by Alisa Shulman-Janiger. The beautiful and rarely observed fluke of a fin whale. This diving behavior was characteristic for this individual, ID326, (for unknown reasons) as she raised her tail on every dive. We also documented three Bryde’s whales, a species we don’t typically encounter frequently in our study area. One individual had a well-healed, large propeller scar caused by a small vessel, a harsh reminder of the threats these animals face on a daily basis. The propeller scar ran down the right side of this Bryde’s whale from the blow hole past the dorsal fin. As part of a collaborative research project funded by the Navy to assess range dependent behavioral responses of fin whales and beaked whales to Navy sonar, we deployed a new type of high resolution dart attached archival tag on a fin whale while on a sonar training range. This tag is designed to stay attached for 2 to 4 weeks and must be recovered to download on board data. Types of data include depth, temperature, 3-D movement, and GPS locations. Greg waits for the fin whale to resurface for a tagging approach. The long carbon fiber pole is used to attach the tag as shown in the video below. So what happens when you have left the island, boated the 55 nautical miles back to the mainland, unpacked all the gear, cleaned up the boat, and literally just summarized the data for the trip, when you receive that all important transmission signal indicating the tag is off the animal? You change your travel plans (thank you Frank and Jane Falcone for making this change seamless), immediately prep and repack the boat, sleep a few hours, leave at 4 am, and pull off a marathon 11 hours from door to door with a 158 nautical mile round trip tag recovery in some sporty sea conditions. The 158 nautical mile roundtrip track of the tag recovery on 13 November 2017. The Navy range is the black polygon on the west side of San Clemente Island. As we headed offshore, the seas picked up as anticipated, and since we had no option but to go in the direction of the tag, we were served up free refills of saltwater face shots. In order to successfully recover this tag in a time crunch, several resources were utilized. First, the tag transmits a signal through satellite which provides a time and position. Second, we were fortunate to have Russ Andrews available to monitor the computer back in Washington. He swiftly calculated drift estimates (essential given the offshore conditions) based on distance and direction between locations and our time of arrival. Third, once in the area, we set up the goniometer which consists of an antenna that receives the signal transmitted from the tag and an output device that provides a direction to the tag. Brenda is using the goniometer to locate a tag. This is not the actual event. It was wet out there! No cameras were sacrificed during this recovery! We made one brief pass through the area, made a turn to port and spotted it floating by an inquisitive gull. Ah yes, we should add that gull as the fourth resource used to retrieve our tag. Birds unknowingly volunteer frequently to help with whale research. With the tag back on board, we exchanged a couple of high fives. It may sound like a lot of effort to deploy and recover this technology but the information that we have retrieved from this one tag is invaluable. We tagged this whale on the range and documented the behavior and movements before, during, and after military activities, the primary goal of this deployment. This tag was worth more than just it’s monetary value. Brenda’s cheesy grin sums up this trip. With the tag back on board, we were thrilled to call our first deployment of this new tag a success! We will be back down in California in January 2018 in support of multiple projects. MarEcoTel would like to thank U.S. Pacific Fleet, Living Marine Resources, Office of Naval Research, Naval Undersea Warfare Center, Southern California Offshore Range, San Clemente Island personnel, and Frank and Jane Falcone for support, assistance, and collaboration. As we mentioned in our last post, we’ve added a new boat to our fleet, the R/V Phoenix: A 2017 Zodiac Pro 750 rigged with twin 115hp Yamaha four stroke engines. We chose this boat based on our past experience with our 2009 Zodiac Pro 650, which has exceeded our expectations. Our 750 has the same internal components (console and bolster seat), which means that all the extra length and width of the boat translates into additional deck space. There were a ton of moving parts associated with this purchase. To start, the boat and two trailers were delivered to the dealer in Ventura California, and we needed to get all three down to Vista, CA for the next phase of this adventure. One of the trailers needs to be shipped to San Clemente Island, the boat needs to have a bow pulpit fabricated, electronics need to be installed, and all this has to be done in a short period of time since we all live in Washington! Thanks to the support of Inflatable Boat Specialists in Ventura CA, Phoenix went from shrink-wrapped on the delivery truck with the tubes off, to prepped and ready for sea trials (including the installation of some of the electronics) in just 2.5 days! Today’s puzzler: How do you move two trailers, one boat and one truck from point A to point B in one trip? This was the puzzle we faced when taking delivery of Phoenix, and here’s how we solved it: Greg went to Ventura to inspect the boat and help layout the installation of electronics. Brenda, Erin and Sebastian went to Vista to gather up gear that would be needed for a boat trip from Ventura to Oceanside, including research gear (we never miss an opportunity to conduct science). On Friday, Brenda and Erin’s dad, Frank, jumped in his truck and drove up to Ventura to meet up with Greg and the boat. Phoenix was launched for initial sea trials (teaser, we hit 48 knots!) and stayed in the water overnight in Ventura. The now empty trailer went back to Inflatable Boat Specialists where the crew used a fork lift to stack the second trailer on top of the first for transport. Early Saturday morning Greg and Frank motored out of Ventura Harbor for the 130 nautical mile run down to Oceanside, while Brenda had the unenviable job of towing the two stacked trailers through Los Angeles, down to Vista. The trip on the boat started with a gorgeous sunrise, and the rest of the day followed suit. While much of the trip was done at relatively slow speeds as part of the break-in procedure, the seas were calm and the trip only took 9 hours. Meanwhile, Brenda arrived in Vista with the two stacked trailers, and since she and Erin did not have the luxury of a forklift, had to use some ingenuity and muscle to get the two trailers un-stacked. Using an engine hoist and elbow grease (with a huge shout-out for the helping hand from Erin’s brother), they got the two trailers un-stacked just in time to head to the ramp to pick up Phoenix from her first full sea trial. We spent Sunday working on smaller details (installation of safety gear, additional electronics, trailer modifications, etc.), as well as some unexpected hiccups. This leads us to Puzzler of the day # 2: What is going to be heavier in the water: a typical galvanized box-frame trailer (which can trap air inside the trailer frame), or an aluminum I-beam trailer which is made from lighter material but has no air trapped inside? This was a question we had pondered before we purchased these trailers, yet the answer was not clear—forums on the web suggested that floating of aluminum trailers was a problem, but mainly for triple axel trailers. However, in our short experience, we can tell you that a tandem axel aluminum trailer is pretty close to neutrally buoyant in salt water. Our trailer was floating back and forth with only a small amount of current inside a well-protected harbor. This is a problem because we are routinely operating at an unprotected boat ramp where seas that will move a heavy single-axle galvanized trailer are common. Today the boat is going to marine fabricators to get a bow pulpit built (an essential piece of equipment for our operations) and a few other odds and ends to complete before flying back to WA mid-week. With any luck (and a bunch more hard work), the boat will be ready for us to use on our next field project in early November.

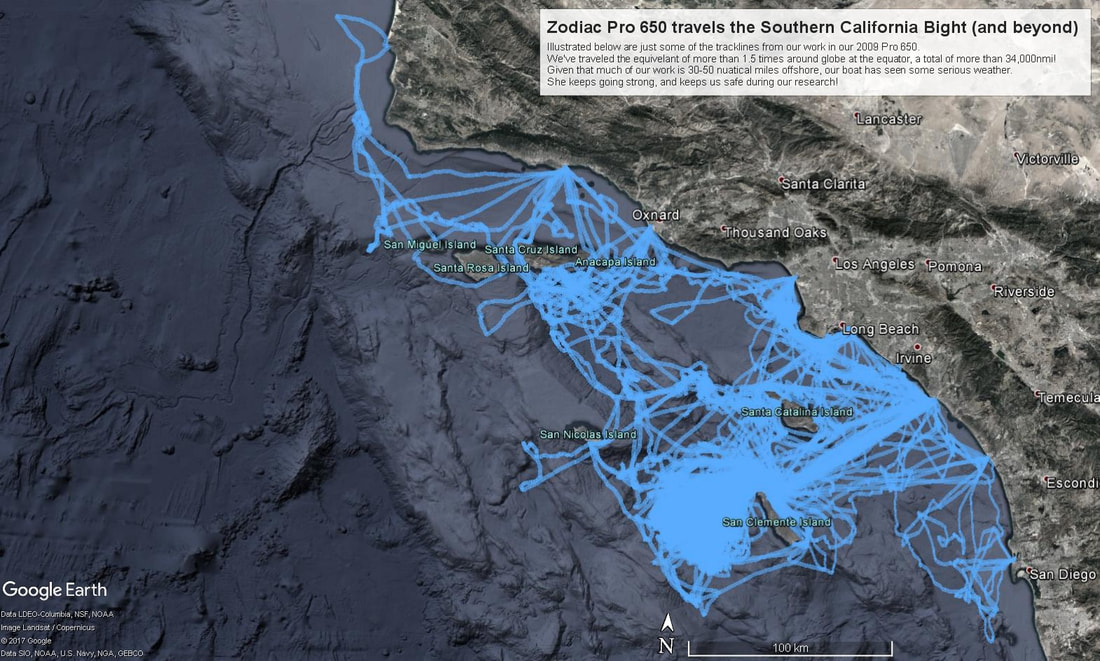

As we mentioned previously, we will take every opportunity to conduct research when on the water. Overall, the transit down was very quiet with only a couple of sightings (common and Risso’s dolphins). It was quiet for marine life, that is. Trash was another story. We collected 44 mylar and latex balloons, debris that is mistaken as food and ingested by animals. Wads of ribbon serve as perfect entanglement traps. This number only accounts for the ones we were able to retrieve. It’s typical for us to find balloons dispersed far and wide and we are just not able to collect everything given time constraints. We find this frustrating. How can you help? Prevent the problem. Don’t release balloons and pass the word on! When you find one, pick it up and dispose of it properly. Balloons can be found everywhere but especially so on the water. Boaters, you have an opportunity to make a big difference. Please consider making a positive change and committing to clean up the environment while out enjoying your day. If we all come together, we can accomplish great things! Anyone who has spent a significant amount of time at sea will recognize the inherent risks of taking a small inflatable boat 40 to 50 miles offshore on a routine basis. Where we operate, there is no protection from the ocean swells, and no large support vessel to pluck us out of the water when the weather picks up. It is rare for us to be operating in conjunction with other vessels, meaning we are out there on our own. Training, experience, and good judgement are key factors in mitigating risks of operating far offshore. Having the right equipment is also critically important. In this blog, we will highlight our current workhorse of a boat, the R/V Physalus, and introduce the carefully chosen, newest member of the fleet, the R/V Phoenix. R/V Physalus (the species name for the fin whale) is a 2009 Zodiac Pro 650, manufactured in North Carolina by Zodiac North America. She is part of a class of boats known as a Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat (RHIB), meaning a fiberglass hull with inflatable tubes surrounding it. RHIBs are inherently stable boats (when operated appropriately), and substantially lighter than a traditional hull of similar size. This results in significantly improved fuel economy—important given our average day at sea covers more than 100 nautical miles (maximum of ~175), and fuel capacity is limited. Twin 75 horsepower Honda outboards power Physalus, so we have enough juice to keep us out of trouble should one engine go down. In the 8 years we have been operating Physalus, we have logged more than 3,000 hours on the water and covered more than 34,600 nautical miles (>40,000 miles or 63,000 kilometers)—that’s the equivalent of having traveled around the globe at the equator more than 1.5 times! During that time, the boat has seen her share of rough weather, including one transit that ended up cracking the hull of a 60’ charter boat that we were working with at the time. Yet, Physalus remained sound and handled the seas with the confidence of the best rough weather boat. In all our time in Physalus, we’ve only had to do minor repairs to the inflatable tubes, and no repairs to the fiberglass hull, despite the tremendous stress put on it. While Physalus will remain our principle research platform, her lack of deck space to accommodate three people in addition to all our research gear, as well as the need for two simultaneous boats for some projects, has led us to investigate adding a second boat to our fleet.

Given our humble origins (in other words, a new-start, small non-profit with no real fundraising mechanism), we initially looked only at used boats. However, our needs in terms of how the boat is configured are pretty specific, and any used boat of sufficient quality we found would have needed costly modifications. We also kept revisiting the fact that Physalus has been a perfect boat for us and we have absolute faith in her abilities to do the job safely. We decided to reach out to Zodiac North America, and in particular, the dealer Inflatable Boat Specialists in Ventura, CA from whom we had purchased Physalus. We sent them a short blurb about our new organization, accomplishments, and history with Physalus, and asked if there was any way they could help support our work. Inflatable Boat Specialists responded immediately and helped us secure a brand new Zodiac Pro 750 with twin 115hp Yamaha outboards at a price point that fit our budget. This new boat, which we have named the R/V Phoenix, is longer and wider than Physalus, providing us with the additional internal space we need for projects which require three personnel on board and/or more research gear. We are spending the next week in California taking delivery of the boat, running sea trials/breaking in the engines, and outfitting her with the electronics, safety equipment, bow pulpit, and other gear we need to have her ready to go to work on our next field effort in November. We’ll post pictures of our new boat in the next few days, but wanted to share the exciting news! Now we just need to find a dealer or generous person(s) to help us obtain a truck to tow the boat! Guess we put the cart before the horse, but that’s always been our style. In the meantime, we’ll continue to rely on the fantastic support of Frank and Jane Falcone, and borrow their truck. new study finds whales react more strongly to sonar used by military helicopters than ships8/29/2017 Scientists from Marine Ecology and Telemetry Research (MarEcoTel) and a team of collaborators have just released the findings of a new study into how whales are affected by military sonar in the journal Royal Society Open Science. This study focused on Cuvier’s beaked whales that live off the coast of Southern California in an area the US Navy frequently uses for training exercises. This is the species most frequently observed to strand in association with sonar use in other parts of the world. Using small, dive-recording satellite transmitters attached to the whales’ fins, they monitored the behavior of 16 whales for periods up to several months, allowing a comparison between how whales behaved when military sonar systems were active and when not in use. This study provided the first large sample of whale behavior with known exposures to ship sonar, which have been studied previously, and to helicopter-deployed sonar that has received much less attention because it is considerably quieter than the sonar used by ships. It also allowed researchers to identify the range of distances to sonar that whales changed their behavior. A variety of behavioral changes were observed, including increased dive duration and an increase in the amount of time between the very deep dives these whales conduct when they are searching for food near the ocean floor. Some of these behavior changes were evident when sonar was used up to 100 km away, though they became more pronounced the closer the sonar was to the whale. One surprising finding was that whales tended to respond more strongly to the quieter helicopter-deployed sonar than to ship sonar at a similar distance. In fact, one whale dove for an astonishing 2 hours and 43 minutes, a new mammalian diving record, while a helicopter deployed its sonar nearby. The authors suggest that these whales may respond more strongly to helicopter-deployed sonar because it is used in a less predictable way. While none of these whales, who appear to preferentially use this region despite the regular disturbance, stranded or died as a result of sonar use during the course of the study, these findings underscore the importance of understanding what these responses mean for the health of both individuals and populations over time. They also suggest that in an area where whales are frequently exposed, the context of sonar is a potentially important predictor of behavior in addition to sound level, which is how sonar impacts are currently estimated. A copy of the paper can be downloaded here (Falcone et al. 2017), or by going to the Royal Society Open Science Website (Falcone et al. 2017). For more information, please contact Erin Falcone ([email protected]) or Greg Schorr ([email protected])  An adult male Cuvier's beaked whale surfaces to breath. Mature males in this species have two small, conical teeth that erupt from the tip of the lower jaw; this whale has stalked barnacles growing from his teeth. Males use their teeth to fight with one another, and older males, like this one, will become covered with long, linear scars as a result. The yellowish coloration on this whale is caused by a type of algae that grows on the whales' skin. We just completed our fourth field effort of 2017. This was our third trip down to San Clemente Island this year. This is a continuation of our long-term study on potential impacts of military activities on beaked whales and other species. The U.S. Navy’s Southern California Anti-Submarine Warfare Range (SOAR), which extends west into the San Nicolas Basin from San Clement Island, is a focal training area within the Southern California Offshore Complex (SOCAL). SOAR consists of an array of 88 bottom-mounted hydrophones that are used for real-time, three-dimensional tracking of undersea vehicles. During this project, we work closely with M3R (Marine Mammal Monitoring on Navy Ranges). Acousticians monitor these hydrophones looking for vocalizing beaked whales and other species to identify areas where we should focus our efforts. Beaked whales vocalize during deep foraging dives. M3R tracks the locations where the vocalizations are occurring to provide the best opportunity for us to locate these animals once they have ceased foraging at depth and return to the surface. This survey effort took place from July 22-30th. During that time, we surveyed 666 nautical miles and spent over 70 hours on the water searching for whales and dolphins. In total, we documented seven species: Cuvier’s beaked whale, humpback whale, short-beaked and long-beaked common dolphin, bottlenose dolphin, bryde’s whale, and fin whale. It was rather quiet for large whales during this survey. We documented one humpback whale, five fin whales (two mom/calf pairs), and a Bryde’s whale. Bryde’s whales are infrequently sighted so we were very excited to document the presence of this animal. While it was pretty quiet for large whales, we were quite successful in locating beaked whales. In all, we had five encounters totaling 9 unique individuals including 2 calves. We started out the trip with some luck as we documented our first encounter of beaked whales on the very first day on the water as we surveyed from the coast out to the island. Later in the week, we were able to deploy a satellite tag on an adult male. In addition to recording dive behavior and locations, this tag provides superior location estimate over a standard Argos tag with the inclusion of Fastloc fast-acquistion GPS developed by MarEcoTel and Wildlife Computers as part of a project in collaboration with the Naval Undersea Warfare Center and was funded by the Environmental Security Technology Certification Program. This was our third deployment of this type of tag on a Cuvier’s, all occurring this year. When we relocated this animal four days later, he was still associated with the same individual from the tagging day as well as a new one. In addition to quality photographs of all animals, we collected nine water samples from the footprints to contribute to a study looking at environmental DNA conducted by the University of Oregon. An additional five biopsy samples were collected from bottlenose and common dolphins to contribute to ongoing studies. Funding for this research was provided by the U.S. Navy Pacific Fleet. Our next field effort will occur in November and we will be back on San Clemente Island.

|

AuthorClick here to learn about our research staff. Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed