|

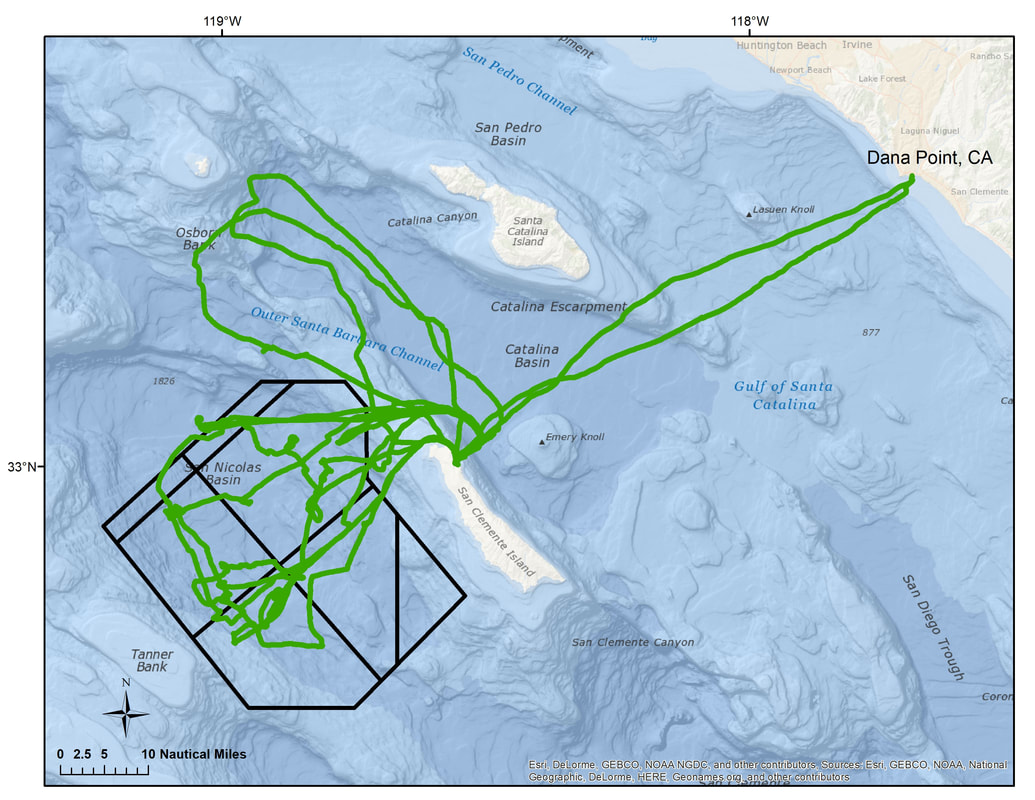

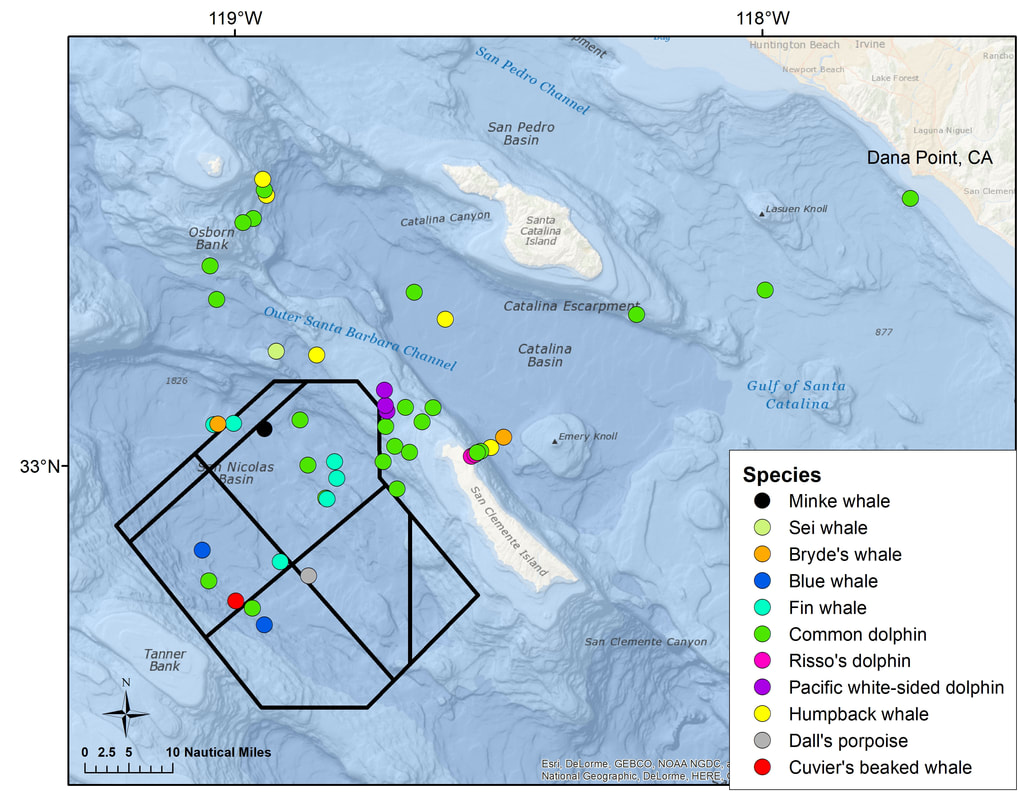

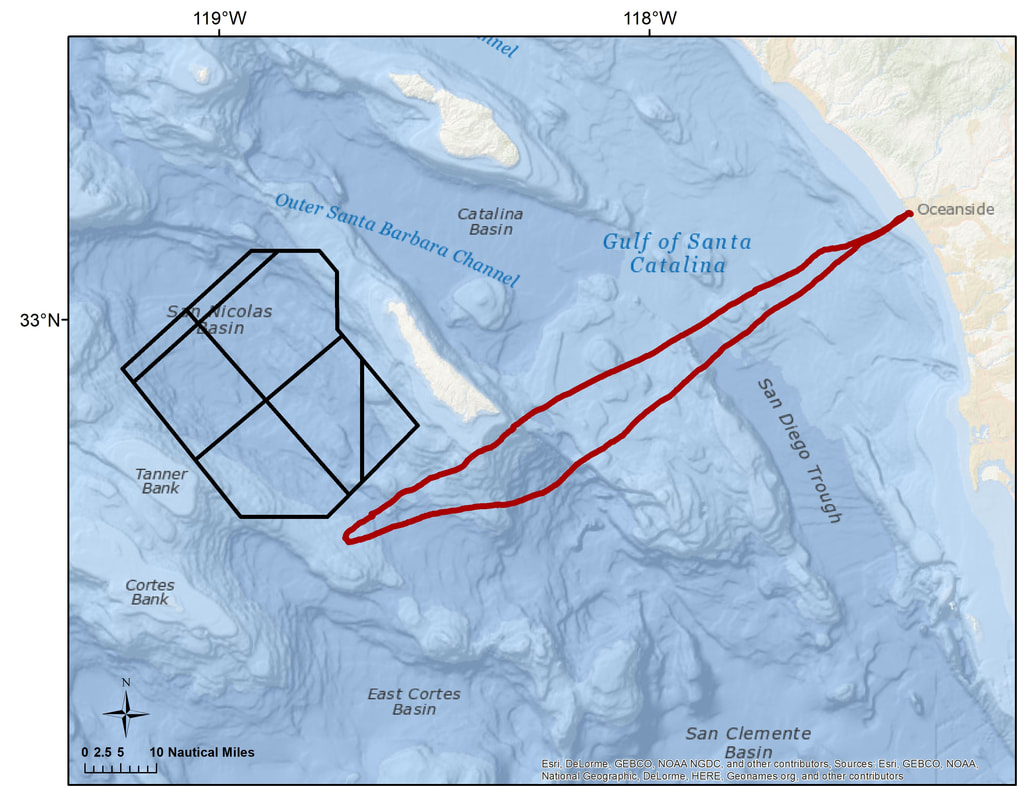

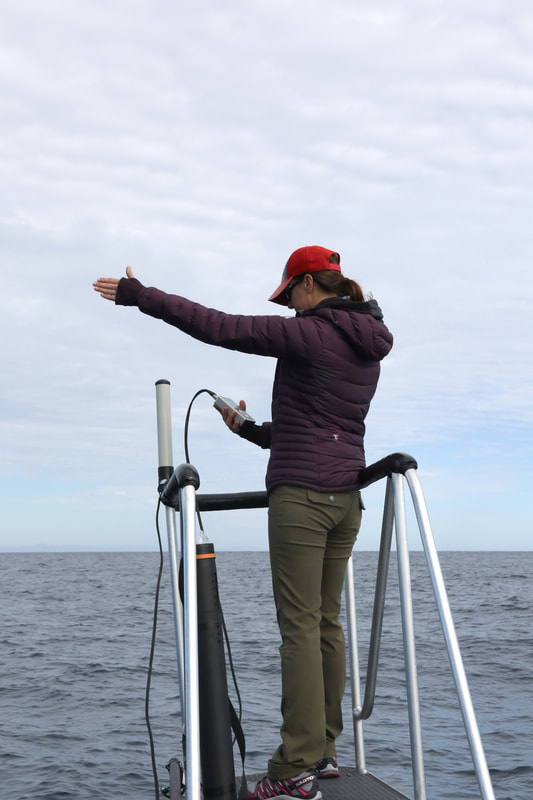

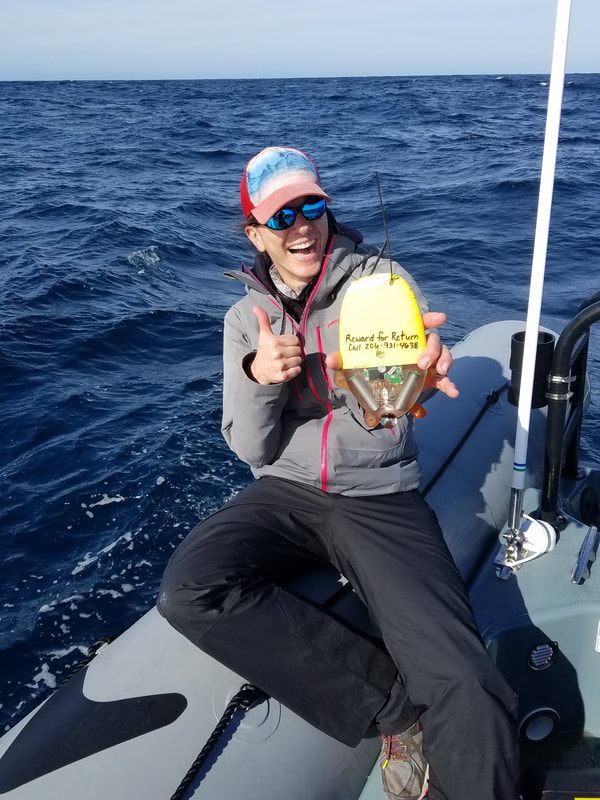

In November, we completed our fifth and final field effort for 2017. This was the first research trip for our new vessel R/V Phoenix. When we arrived in California at the start, we had to hit the ground running in overdrive (although when don’t we!) in order to finish up the last round of installations and configurations in order to have her science ready. With tasks completed in time, we packed her up with our equipment and food and were immediately pleased with what felt like an infinite amount of storage space (don’t worry R/V Physalus, we still love you). With her ample space for equipment and persons, her speed to get us on scene, and her comfort when working in rough conditions, she quickly proved to be an invaluable asset to our research and conservation efforts. Greg and R/V Phoenix in Wilson Cove, San Clemente Island. During this project, we spent 73 hours on the water and surveyed 868 nautical miles. We documented 53 sightings of 11 species: minke whale, sei whale, Bryde’s whale, fin whale, blue whale, humpback whale, Cuvier’s beaked whale, Risso’s dolphin, common dolphin, Dall’s porpoise, and Pacific white-sided dolphin. Survey effort and sightings from the November 2017 project. It was a quiet project for beaked whales. In fact, we only had one encounter of a single animal for one surfacing despite acoustic detections. We define “beaked whale weather” as a Beaufort seastate 2 or less with minimal swell. They are cryptic animals and near glass calm conditions are needed to see, hear, and approach in time before they slip back down for another dive. These dives can range from 20 min to 2 hours depending on their behavioral state with surface times only averaging 2 minutes. The lack of visual sightings for this trip can be attributed to a fair chunk of uncooperative weather. Even rain made an appearance which is really nothing abnormal for us Pacific Northwesterners, but on one lucky morning, we were gifted one of the most vibrant rainbows either of us have seen. Unfortunately, there wasn't a beaked whale at the end of it. Searching, searching, and more searching for beaked whales. Greg remains focused despite the background show. We had a few noteworthy encounters this trip. The first was of a fluking fin whale. Unlike whales such as humpbacks, blues, and grays, this is not a common occurrence for this species. In fact, for one of us, this was only the second time this was observed, the first time being 19 years ago in another ocean! This whale is a genetically confirmed female identified as ID326 in our catalog and has been sighted in Southern California nearly every year since 2009. This whale is so unique that when we posted this fluke photo, she was immediately recognized as “Flukey” by Alisa Shulman-Janiger. The beautiful and rarely observed fluke of a fin whale. This diving behavior was characteristic for this individual, ID326, (for unknown reasons) as she raised her tail on every dive. We also documented three Bryde’s whales, a species we don’t typically encounter frequently in our study area. One individual had a well-healed, large propeller scar caused by a small vessel, a harsh reminder of the threats these animals face on a daily basis. The propeller scar ran down the right side of this Bryde’s whale from the blow hole past the dorsal fin. As part of a collaborative research project funded by the Navy to assess range dependent behavioral responses of fin whales and beaked whales to Navy sonar, we deployed a new type of high resolution dart attached archival tag on a fin whale while on a sonar training range. This tag is designed to stay attached for 2 to 4 weeks and must be recovered to download on board data. Types of data include depth, temperature, 3-D movement, and GPS locations. Greg waits for the fin whale to resurface for a tagging approach. The long carbon fiber pole is used to attach the tag as shown in the video below. So what happens when you have left the island, boated the 55 nautical miles back to the mainland, unpacked all the gear, cleaned up the boat, and literally just summarized the data for the trip, when you receive that all important transmission signal indicating the tag is off the animal? You change your travel plans (thank you Frank and Jane Falcone for making this change seamless), immediately prep and repack the boat, sleep a few hours, leave at 4 am, and pull off a marathon 11 hours from door to door with a 158 nautical mile round trip tag recovery in some sporty sea conditions. The 158 nautical mile roundtrip track of the tag recovery on 13 November 2017. The Navy range is the black polygon on the west side of San Clemente Island. As we headed offshore, the seas picked up as anticipated, and since we had no option but to go in the direction of the tag, we were served up free refills of saltwater face shots. In order to successfully recover this tag in a time crunch, several resources were utilized. First, the tag transmits a signal through satellite which provides a time and position. Second, we were fortunate to have Russ Andrews available to monitor the computer back in Washington. He swiftly calculated drift estimates (essential given the offshore conditions) based on distance and direction between locations and our time of arrival. Third, once in the area, we set up the goniometer which consists of an antenna that receives the signal transmitted from the tag and an output device that provides a direction to the tag. Brenda is using the goniometer to locate a tag. This is not the actual event. It was wet out there! No cameras were sacrificed during this recovery! We made one brief pass through the area, made a turn to port and spotted it floating by an inquisitive gull. Ah yes, we should add that gull as the fourth resource used to retrieve our tag. Birds unknowingly volunteer frequently to help with whale research. With the tag back on board, we exchanged a couple of high fives. It may sound like a lot of effort to deploy and recover this technology but the information that we have retrieved from this one tag is invaluable. We tagged this whale on the range and documented the behavior and movements before, during, and after military activities, the primary goal of this deployment. This tag was worth more than just it’s monetary value. Brenda’s cheesy grin sums up this trip. With the tag back on board, we were thrilled to call our first deployment of this new tag a success! We will be back down in California in January 2018 in support of multiple projects. MarEcoTel would like to thank U.S. Pacific Fleet, Living Marine Resources, Office of Naval Research, Naval Undersea Warfare Center, Southern California Offshore Range, San Clemente Island personnel, and Frank and Jane Falcone for support, assistance, and collaboration.

3 Comments

4/25/2018 17:27:41

Whales are scary. Sure they are friendly and smart but I don't care what everyone else say. I am afraid of whales. If I see them I think I am going to faint. Even the smaller ones scare me to death. Even so, being afraid of something does not give anyone the right to hurt that creature or drive it away for our own convenience. I wish more people will understand why I can't get my hands to kill cockroaches and anything that crawls, not even the head lice on children's hair. It just feels wrong. What do we do if it tries to hurt us? Ask ourselves "Can they really do that?"

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorClick here to learn about our research staff. Archives

August 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed